Scientists at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) Animal and Human Health program and a newly established platform that aims to transform animal health services and solutions in low-and middle-income countries (TAHSSL) have developed a panel of new procedures for measuring the immunological activity of livestock blood samples to a specific pathogen. Known as antibody assays, it uses antigen-specific blood serum from animals to detect any activity against the pathogen that causes disease in the livestock.

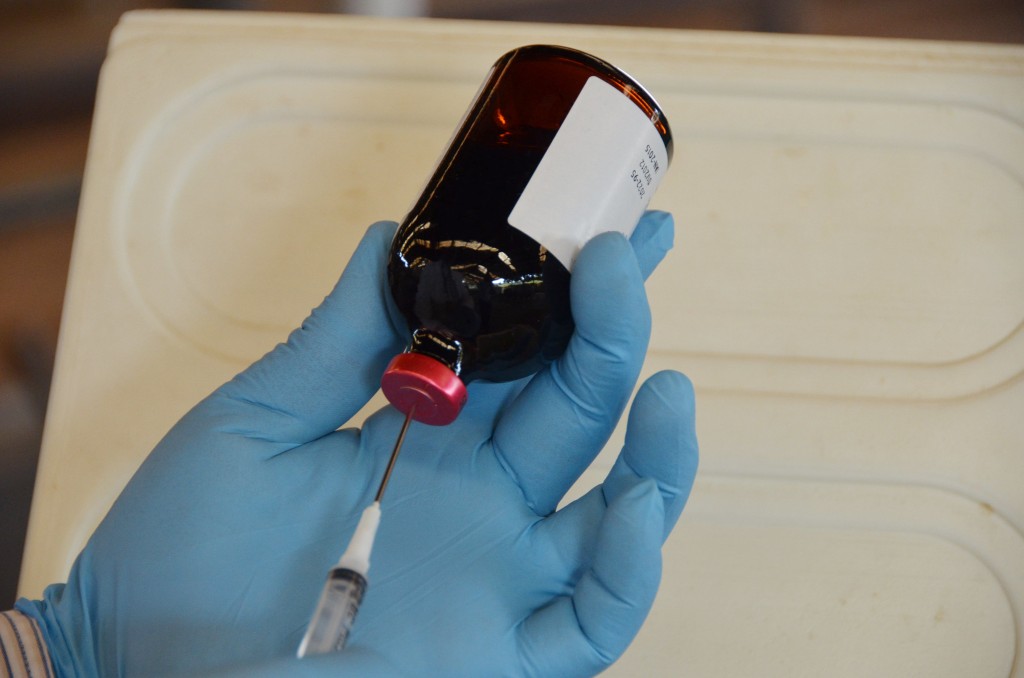

The tests, known as an antigen-specific serological tests, are helping scientists detect the presence of an immune response to pathogens and antigens that can be used to develop vaccines against important livestock diseases such as East Coast fever (ECF).

ILRI research scientists have been using similar assays for decades to test vaccine efficacy, however the modified assays are more efficient. Recently, through ILRI’s Research Methods Groups, the scientists have been addressing the efficacy of vaccines candidates by applying these assays in an effort to identify what parts of the immune response are important for protection. This will help scientists move away form using animals to using in vitro assays, and dramatically reduce the use of animals in any given experiment.

Led by ILRI’s Anna Lacasta and TAHSSL coordinator Musa Mulongo, the researchers have modified the standard assay to detect specific antibodies against an antigen, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), used in the past to now measure the amount of specific antibodies in absolute quantities (micrograms per ml). This standardized test allows a more accurate comparison of samples from different cattle.

Similarily, seroneutralization assays initially developed in 1979, were used to detect antibody activity against the pathogen. However, the method had several limitations in terms of reproducibility for each time the assay was performed with the same samples using fresh material, or the use of live animals to test the activity of the antibodies. The new assay is overcoming such limitations, it is more accurate and reduces the time to get results from 14 days to two.

Applied in combination, both improved assays will allow more sensitive and specific comparison of the presence of antibodies that are able to neutralize the pathogen and avoid infection. These antibodies can be found in the animals blood after an infection or after vaccinations and to help drive the development of novel vaccines.

By using cattle sera at ILRI, the new method will be used to evaluate the capacity to prevent the pathogen infecting the animals by themselves or in combinations and without the use of this assay, one would need to use close to 1500 animals in any given experiment and this method cuts down the use of animals to forty.

This assay development is being supported from the CGIAR Research Program on Livestock, the CGIAR Trust Fund and by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation who have recently supported a technological platform to generate veterinary products and transform animal health services and solutions for low-and middle-income countries (TAHSSL).

For more information, contact Anna Lacasta (a.lacasta@cgiar.org)